Talk: All my hope on God is founded

Education is a central aspect of the Cathedral’s mission. We offer opportunities for learning, dialogue and engagement with issues of public debate.

At the Cathedral, people of all ages can learn about faith and discipleship. We run a Sunday School and are developing work with young people; there are occasional study groups and Lent Lectures.

The Cathedral is a theological and educational resource for the Diocese, supporting the work of clergy and parishes. The Cathedral works with the Diocese in planning and delivering an annual summer school.

Working with other institutions in and around Stag Hill, for example the University of Surrey, the Cathedral is committed to engaging with issues in the public sphere (including social responsibility, science, ethics, the arts and inter-faith dialogue). There will be an annual series of talks alongside seminar based groups.

Transcripts of these talks are, where possible, included below.

For details of forthcoming talks, please see the Cathedral Diary and What's On

- Speaker:

- Date:

- Thursday 26th March 2015

- Service:

- Lent Talk: Do not be afraid

Our Lent Lectures at Guildford Cathedral have responded to the phrase 'Do not be afraid': hearing it perhaps as a challenge, an invitation, an imperative or word of assurance. We've been thinking about Catherine Clancy's exhibition on that theme (on display at the Cathedral this Lent). We have been considering which images draw us in, either because they resonate with us or intrigue us; and which paintings we find difficult because, perhaps because they're too bright or because we struggle to find a point of connection.

This Lenten journey has taken us from courage to a hesitant and generous love; from the presence of God in clouds to the peace of Christ in storms. We have thought about fear, grace and suffering; renewed vision, resilience and creativity. And now on the cusp of Holy Week, as we turn our hearts and minds to Jerusalem, I will contemplate the nature of hope. Hope is shaped by scripture, poetry and art; drawing together our traditions, experiences and imaginations. It's an opportunity to think about where God meets us in the complexity of our lives - and how his Spirit draws us onwards in the face of death to new life.

If we type the word hope into Google, a whole range of images are thrown up: we might find a rather energetic figure looking to the future: outstretched arms embracing new horizons as day breaks. It looks full of optimism, if a little romantic. Perhaps we stumble across an image that depicts new life in inauspicious circumstances; flourishing or growth against the odds.

Some images have a recognizably religious feel: candles burning - we don't know why they're lit; the light is flickering in the darkness. Flames as a sign of our prayers offered amidst confusion, curiosity, hope and love; tentative or assured expressions of faith made by human beings on a journey.

There are resonances of Jesus Christ, light of the world; perhaps in lighting a candle we are placing our trust in God; reaching out towards or acknowledging his presence near us. We staking a claim; naming a hope when we can least articulate it.

Finally, there's an image of sensing the dawn as it breaks; we feel the light pouring in as well as seeing it; even in the darkness, even in brokenness something of the beyond is breaking in.

Hope is a University and a Hospice: places of learning and living life in the face of death. Hope is a radio station; a Swedish clothing company; a creative design agency. It's associated with inspiring or encouraging listening; an alternative lifestyle brand; developing corporate identities. Turn to Wikipedia - the source beloved of student and scorned by tutors - we find hope described as an optimistic attitude of mind based on an expectation of positive outcomes related to events and circumstances in one's life or the world at large.

Psychologists, leaders, literary critics and cultural commentators all have something to say about 'hope'. But surely there is more to it than that? Hope isn't a brand, a naive wish fulfilment or transference theory. However, it is important to acknowledge this dilution of hope; it might help us to make connections whilst witnessing to the good news of Christ.

We glimpse part of that 'more than' when we kept the feast of the Annunciation to the Blessed Virgin Mary: it's a day that in a sense takes us to the heart of hope. When this joyful celebration falls in Passion-tide, as it does this year, there are deeper resonances. We can't simply romanticize this moment of encounter - between a young woman and an angel. It is an occasion of thanks and praise; yet Mary needs to ponder the mystery and cost of the message. Following a greeting full of honour and grace, the words that fall from Gabriel's lips are 'do not be afraid'. His assurance enables Mary to hear this promise with faith.

The Annunciation- Fra Angelico (1387-1455)

By the power of the Spirit she conceives. Yet, as the words of the Preface express it: From the warmth of her womb / to the stillness of the grave / he shared our life in human form. To sing, 'all my hope on God is founded' is to fix our eyes on Christ: our prayer continues in him a new light has dawned upon the world / and you have become one with us / that we might become one with you.

We know the incarnation of God's Son by the message of angel; we pray that by his cross and passion we be brought to the glory of his resurrection. That is the foundation of our hope: a God whose generous love is made known to us not just in the mystery and awe of the created order, but in abiding with us. Jesus is Emmanuel, God with us. It is not just that 'with-us-ness' that gives us hope; but it is the assurance of forgiveness and the renewal of vision. Whatever we face and endure now, is not the ultimate reality.

During Lent, we have been challenging to think about what it means to be courageous, the indifference of the natural world and the storms and clouds that assail us - those internal and external pressures and situations that overwhelm us. In all this we have been encouraged to think, by Dianna Gwilliams, Derek Holbird, Steve Summers and Andrew Bishop to think about how we respond and endure. Do we rely on inner strength or find unexpected moments of grace? Do moments of hesitation enable us to glimpse love? Where to find an anchor point or harbour in a storm, or do we ride it out? Do we rise above the clouds and find glory and presence of God?

Catherine Clancy: The storm took my soul away (2014)

What do we hope for?

If it isn't optimism, how do we cultivate it?

If it is a spiritual virtue, what practical difference does it make to our lives as disciples of Christ?

The biblical vision of hope often emerges in the face of adversity. Naomi says to Ruth and Orpha Even if I thought there was hope for me, even if I should have a husband tonight and bear sons, would you wait until they were grown? [Ruth 1:12-3]. In the face of losing her sons, she seeks to liberate her daughters-in-law to continue their lives: even if she could bear children, how could these adult women wait, putting their lives on hold. The lack of hope in relation to the human condition forces them to make choices about where they place their trust in the future.

The books of Job, the Psalms and Proverbs are full of hope and despair: Let the stars of its dawn be dark; let it hope for light, but have none (Job 3:9). There is disappointment and loss; yet there is also confidence because of hope. There is hope for the tree that is cut down and which sprouts again; Job is assured of protection and rest because there is hope, whereas the only hope of the wicked is to breath their last.

The psalmist contrasts the vain hope of the war horse by its great might it cannot save (Ps. 33:17), whereas those who trust God place their hope in his steadfast love (Ps. 33: 18). Hope is placed in God - in his word, in the fulfilment of his commandments; it becomes a source of blessing and gladness. Hope is associated with wisdom and a vision for the future (Proverbs 24:14). The prophets Isaiah and Jeremiah contrast the misplaced hope in other gods or rulers with the call to wait patiently on the Lord I will wait for the Lord... I will hope in him (Isaiah 8:17).

There’s a contrast between placing our hope in the fleeting, contrary and disappointing things of this world and the steadfastness of God. There is a reciprocity undergirding these hopes: patient waiting and obedience to commandments are expressions of hope. They are generative because they are placed in God - the one who is faithful and steadfast. This echoes in the Gospels - Jesus Christ is the one in whom the Gentiles will hope (Matthew 12: 21); in contrast Jesus speaks of the superficiality of human relationships based on exchange and hope return (Luke 6:24).

Acts and the epistles are full of hope: in the light of the resurrection, hope seems to overflow: Hope is in the promise of God, which Paul affirms as he faces his trial (Acts 24: 15; 26:6). Hope is set on Christ, that we might life for the praise of his glory (Ephesians 1:12); it is the source of our calling - being one body, in one Spirit; rooted in fellowship and faith in the Lord (Ephesians 4:4).

Paul hopes to meet his brothers and sisters, for them to meet Timothy and others; but such fellowship is in Christ (Philippians 2:23; 1 Timothy 3:14). Hope has a heavenly focus - a longing for the new creation. Yet, hope isn't just about eternal life (Titus 3:7). There is a very real impact in the present: living hope leads to holy living (1 Peter 1:3, 13).

In struggles, hope is in the living God; the Saviour of all people. It is a hope that is a steadfast anchor; hope in Jesus Christ; an invitation, perhaps, to fix our eyes on him when storm, clouds, fear and disaster assail us.

Very often when we think about hope, we link it consciously or not to faith and love - thinking of Pau's letter first letter to the Corinthians, chapter 13: Faith, hope and love abide, these three, but the greatest of these is love. We might think of bracelets bearing a cross, anchor and heart. So perhaps we find Watts' painting haunting because he considers hope alone.

G. F. Watts: Hope (1886)

This painting is perhaps one of his most popular and certainly the most famous. I spent some time at Watts Gallery on Saturday gazing at this blindfolded young woman whose eyes couldn't meet mine. She is wearing a pale blue robe; sitting precariously on what seemed to me at first a rock, but perhaps it's a globe. She is stooping awkwardly, even uncomfortably; bent almost double, folded in on herself. She cannot see, but she can touch and hear. She seems to be paying absolute attention to the lyre she's holding. She is clinging on to it, straining to hear the faint sound it makes (the note she can make) on the last remaining string. A very melancholy, tuneless reverberation made by finger plucking a sting in the air.

Is Watts bravely, controversially, conceiving of hope without either faith or love? Is it perhaps a visual representation of Arnold's 'Dover Beach' ? His words reverberate: The Sea of Faith / Was once, too, at the full, and round earth’s shore / Lay like the folds of a bright girdle furled. / But now I only hear / Its melancholy, long withdrawing roar, / Retreating, to the breath / Of the night-wind, down the vast edges drear / And naked shingles of the world. I would say not: there is a residual light and peace in Watts’ image. There may not be certitude – but amidst what Arnold calls the darkling plain there is a longing for help in pain, a light which breaks in.

Although the figure of the woman occupies much of the canvas, there is an expanse of space which seems to exaggerate her alone-ness. She is a solitary figure - abandoned, exiled, escaping or seeking safety. Even so, that its perhaps not wholly hopeless. As we have seen, in the scriptural tradition hope is not absent in adversity. Even when the exiled people of Israel hung up their harps, God's love remained faithful. They were called to sing, as Bishop Andrew put it at his induction, a beautiful song.

Is there a sense of hope within this young woman? Perhaps it isn't a hope that is rooted in her own emotional resilience or inner strength; perhaps there is a hope beyond the constraints of her circumstances. There is a single star in the sky; a single still point. She cannot see it. As Paul writes to the Romans: In hope we were saved. Now hope that is seen is not hope. For who hopes for what is seen? But if we hope for what we do not see we wait for it with patience (8: 24-25).

Hope is somehow staking a claim in a reality beyond our senses; places our trust in God's love even when we wait for the fulfilment of God's purposes. He goes on to describe the way in which the Spirit helps us in our weakness for we do not know how to pray as we ought, but that the very Spirit intercedes with sighs too deep for words (8:26-27). God searches the heart; knows the Spirit. God is faithful. We know, says Paul, that all things work together for good.

Watts’ painting wasn't unanimously well received. K . Chesterton found it to be so bleak that it might just as well been called ‘Despair’. Some found the allegory obscure and the paint clumsy (N. Tromans, Hope: The Life and Times of a Victorian Icon, p. 20). Others like the poet Emily Pfeffer offer a Christian response: she speaks of scattered tones which may surprise / Thee with a vision to inform the sense; / And gift thee out of wreck and wrong withal / To see the city of God to music rise. Its melancholic, dreamlike or tragic qualities leave it open to interpretation.

The physical absence of a depiction of love and faith, as feminine forms bringing harmony and balance is more honest. Paul cries out in the midst of hardship and distress, persecution and nakedness: who can separate us from the love of Christ? Nothing is his answer. Perhaps this image is in effect an interpretation of that Pauline assurance: it evokes the depth of human despair and abandonment, and yet conveys our capacity to endure, to retain a vision of a better world. We do this because God remains faithful; because his love in Christ reaches out to us in our fear and desolation; because his Spirit cries out within us.

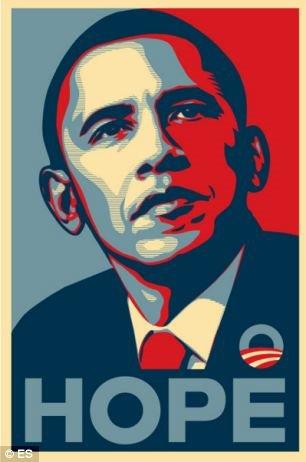

I was reminded this week of the global impact of this painting: one young Barack Obama heard Jeremiah Wright preach a sermon in 1990 called 'Audacity to Hope', inspired by a lecture on Watts' painting. He said with her clothes in rags... her harp all but destroyed... she had the audacity to make music and praise God... To take the one string you have left and to have the audacity to hope. Obama adopts this theme for his book 'Audacity of Hope'. In his speech at the Democratic National Convention in 2004, he speaks of faith in simple dreams and small miracles; the legacy of forebears and the promise of future generations.

www.huffingtonpost.com/ben-arnon/how-the-obama-hope-poster_b_133874.html

There are hints that this isn't just the resuscitation of an American Dream for he says: I'm not talking about blind optimism here, the almost willful ignorance that thinks [the]... heath care crisis will solve itself if we just ignore... I'm talking about something more substantial. It's the hope of slaves sitting around a fire singing freedom songs...Hope in the face of difficulty, hope in the face of uncertainty, the audacity of hope: in the end, that is God's greatest gift to us... a belief in things not seen, a belief that there are better days ahead [Washington Post online].

Barack Obama found a renewed political vision in this audacious hope: but we know the outworking of this in domestic policy and on the national stage is fraught, complex and disappointing. Expectations were set so high; the rhetoric so compelling: do we jettison hope or recast it? How do we hope for the right things – living with the contingencies of our life – personal, national and international?

We have talked about finding still points in the midst of confusion; of glimpses of assurance. Such language is reminiscent of T. S. Eliot's 'Four Quartets'. In 'East Coker', Eliot draws us urgently into a journey through darkness towards a deeper communion. He invites us to pay uncompromising attention to flesh and bone, waves and whispers, houses and fields, to time, rhyme, music and dancing. This is the stuff of life - we would add our own concerns and joys to that list.

He urges us to seek the eternal moment amidst the disorder of the natural world; he looks beyond the vacant interstellar spaces, beyond the motives, flaws and pettiness of distinguished human lords. Paradoxically, he writes that: We must be still and still moving / Into another intensity. We are perhaps called to pay attention to what confronts us; to the waves, clouds and storms; yet somehow moving forward into the intense communion of God's love.

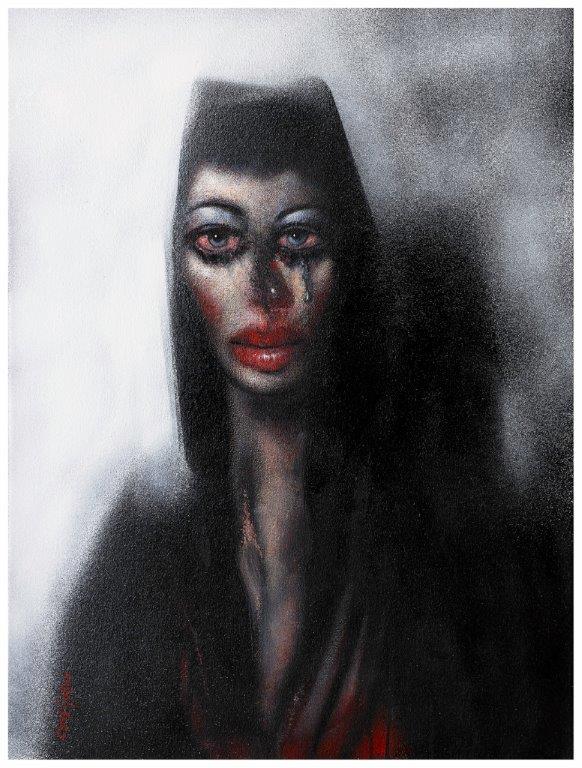

Catherine Clancy: Dark Night of Crucifixion (2014)

Clancy's 'Dark night of crucifixion' captures something of both bearing with and moving on through what Eliot calls the dark cold and the empty desolation / The wave cry, the wind cry, the vast waters. In the darkness, there is that scorching flash of colour - a crown of thorns, a shedding of blood. Might that be a source of hope; of divine love with us, holding us and drawing us onwards?

Catherine Clancy finds in Eliot's verse a wayfarer to explore with us the exhortation, assurance or longing within the phase 'Do not be afraid'. He knows of light and of reference points; the disturbance of storms and the disorientation of being overwhelmed. Dawn points, and another day / Prepares for heat and silence. Out at sea the dawn wind / Wrinkles and slides. I am here / Or there, or elsewhere. In my beginning.

He writes too of our human fears: fear of fear and frenzy, their fear of possession, / Of belonging to another, or to others, or to God. In darkness, wind and storm, Clancy confronts us with the fear; yet that radical de-centring allows us to seek after wisdom. Those things are intimately related for the only wisdom we can hope to acquire / Is the wisdom of humility: humility is endless.

Clancy's paintings echo the traces Eliot's journey of assurance in the midst of all that disrupts; hope in the midst of turbulence; and the longing of waiting in silence. Eliot confronts the intolerable wrestle / with words and meanings in pursuit of wisdom, allowing images to resonate, disturb and delight. Clancy takes us in to density of darkness in such a way as to compel us to attend; to risk stillness amidst movement; allowing our eyes to adjust to see the incremental breaking in of light.

Clancy describes this as negative capacity leads to surrender and trust; for creativity and renewed perspective. Amidst the darkness and storm, it is the Spirit that comes like wind that moves across the deep like a flash of violet. It is the Spirit who gives us life; bringing us to a safe harbour, drawing us to love. It is the Spirit that brings a blinding brightness; evoking in us the depth of reverent praise.

At a human level, our hopes and loves are often thwarted, transient or unfulfilling; we focus on the wrong thing. Wait without hope / For hope would be hope for the wrong thing, writes Eliot, inviting us to suspend our human inclinations. This is so hard to do. We long for trust in our relationships – whether in the intimacy of our personal lives or the pressures of our working life. We might hope for short term satisfaction – believing the advertisers that we just need this experience or product. We might be fearful about our financial security – about our pensions and mortgages. Those concerns occupy our institutional life too – as we face questions about our national vision in the run up to a General Election; as we think about the priorities for mission and ministry within our parishes, diocese and cathedral.

Do we hope for the wrong thing? So often what we think of as financial or personal issues are in fact spiritual ones. How can we encourage one another to have the assurance to place God centre stage? To fix our eyes on Christ, as Andrew described it last week; to discern where the Spirit might be leading us. Sometimes it does feel as if we are stepping into the darkness – as clouds and waves encompass us. And yet, we abide in the assurance that all hearts to love will come.

In the risk of stillness we find meaning; the beyond, the transcendent, the eternal breaks in. A new hope emerges in the face of the turbulence. So the darkness shall be the light, and the stillness the dancing writes Eliot, as he grapples with finding faith, hope and love in the waiting.

Catherine Clancy: All Hearts to Love Will Come (2014)

This paradox of movement and attention finds its focus in Good Friday. In Jesus Christ, God's love for the world is poured out: Beneath the bleeding hands we feel / The sharp compassion of the healer's art. Clancy expresses this intensity, union and deeper communion in darkness, waves, warm haze and light.

Love is most nearly itself

When here and now cease to matter.

Old men ought to be explorers

Here or there does not matter

We must be still and still moving

Into another intensity

For a further union, a deeper communion

Through the dark cold and the empty desolation

The wave cry, the wind cry, the vast waters

Of the petrel and the porpoise. In the beginning is my end.

The sharp compassion of the healer’s art takes us to the depths of human despair; and to the foot of the cross. Where we fear that there is no remedy, God’s love meets us. When we are spent and exhausted, there hope is renewed. These things are held together in the mystery of the incarnation – from the warmth of the womb to the darkness of the tomb.

Chris Gollon's exhibition "Incarnation, Mary and Women from the Bible" was at Guildford Cathedral last year and now on a national tour of cathedrals. His work has a tremendous capacity to draw us into stories and moments that are unanswered and unresolved. These paintings capture sexuality and power, longing and loss, tenacity and exhaustion, tenderness and violence. Gollon pays attention to the detail: to little things; to nameless women and those women whose stories we think we know. His images have compelling intimacy and the horror of brutality.

Gollon enables us to inhabit even familiar stories without knowing the outcome; or rather, despite knowing what happens next, we are caught up in glimpses of prayer, sorrow, contemplation or bewilderment.

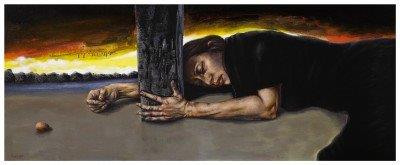

Chris Gollon: ‘There Was No Remedy (Gollon Version)’ 2012

In this image, he refuses to resolve the moment for us. Here is a woman whose expression conveys a depth of hopelessness. Perhaps the honesty of that is strangely liberating – it expresses a truth that sometimes we find ourselves beyond words. We cannot escape the reality that unfairness, cruelty, illness and even our own tendencies to shut ourselves off can isolate us. In those moments we can do nothing other than go through it.

That waiting creates a capacity to endure; it forms our character. It is sometimes all there is: this abiding in love; this refusal to collude with a naive optimism; this facing of the darkness as the tears dry on our cheeks. Gollon makes us fix our gaze on one for whom there was no remedy. As she abides and endures, Paul's words to the Romans echo within us: suffering produces endurance, and endurance produces character, and character produces hope, and hope does not disappoint us, because God's love has been poured into our hearts through the Holy Spirit that has been given to us (Romans 5:3-5).

Hope is the confidence placed in God: which faith expresses and which love makes known. Such confidence, the substance of such hope, flows from an experience of God. This experience of being accepted is not just in relation to Paul’s personal encounter with the risen Lord. He is expressing a conviction rooted in the content of faith. He is convinced about human reliance on God in the midst of suffering. Patience is not for him a stoical attitude; rather it is about assurance in the face of adversity which leads to greater resilience and character. Justine Allain-Chapman in her book ‘Resilient Pastor’ takes this argument further to say it also increases our capacity to be altruistic. She argues this not just on the basis of Scripture and the Christian tradition, but psychological studies.

Hope does not disappoint because we are not reliant on human resources, but on the love of God poured into our hearts by the Spirit. Paul invites us to trust in God’s love poured out in creation; that love made manifest in Christ as life-giving power; and in the Spirit as the channel of that ongoing sustaining and character forming love.

That overwhelming love is revealed in the cross: here love human and divine is poured out. Mary is emotionally exhausted and spiritually spent; yet there remains a physical strength. In boldly choosing to focus on the base of the cross, Gollon intensifies the harrowing reality of her suffering; but he also makes us pay attention to the faithfulness and endurance of a woman whose life is woven into the Gospel, whose story continues to arouse our curiosity. We have to wait with her as she waits alongside her beloved Lord.

Chris Gollon: Mary Magdalene at the Base of the Cross (2013)

She is named as Mary Magdalene - a woman who is restored to wholeness and dignity through her encounter with Jesus. The stories of other nameless women are attributed to her: stories of sexual impropriety or exploitation; of penitence and restoration; of mental anguish and healing. She is the type of women who witness to who Jesus is: lavishly anointing his feet with oil and tears; crying out with fear and despair on the way to Calvary; waiting at the cross, near the tomb and in the garden. Our imaginations are shaped by all that is told in memory of her; all that is told points to a reality beyond our imagining.

In this particular painting, Gollon draws us into a moment of sheer endurance in the face of suffering. Mary has refused to walk away. Her exhaustion is a moment in a vigil that is yet to come to an end; her whole being responds to the one who transformed her life in and through love. Love has been poured into her heart by Jesus - the one who is the fullness of God's love made perfect in human weakness. Gollon presents us with a woman whose character has been formed by sorrow, acceptance, loyalty, challenge and compassion. Her character is seen in sinew and touch; in her poise and closing eyes.

Mary Magdalene has both passed beyond and also anticipates this moment without remedy. She has confronted the horror of the cross and sleep weighs heavily on her. Yet when she awakes she will stand bewildered before an empty tomb; she asks through her tears 'where have you laid him?' She waits in the hope of being able to treat her beloved Lord with dignity in death. Yet before we reach the garden, Gollon refuses to allow the darkness to overcome. As in Watts' 'Hope', this woman cannot see - her eyes closed in exhaustion; caught up in the deep sleep of grief. Unlike 'Hope', she is not making a note on her broken lyre; instead her hand grasps the base of the cross. Here the love of God stakes a claim in the midst of all that appears calamitous, hopeless and final. For Watts, light was a single star; here light breaks in like the dawn.

As the poet Micheal O'Saidhail writes in ‘Knowing’ A majesty and awe, but even more the wonder/That something is where nothing might have been. Even in our brokenness a beyond is breaking in. Vivid oranges and yellows infuse this moment with hope. A hope that does not disappoint because it is rooted in the love of God which is being poured out in sorrow and at the end, at the moment of final breath. It is a love being poured out in endurance that means this moment is also the beginning of life. Love has taken root in Mary's heart; a love that she will recognize when her risen Lord calls her by name. She will bear witness to what she has seen - love welling up in her heart.

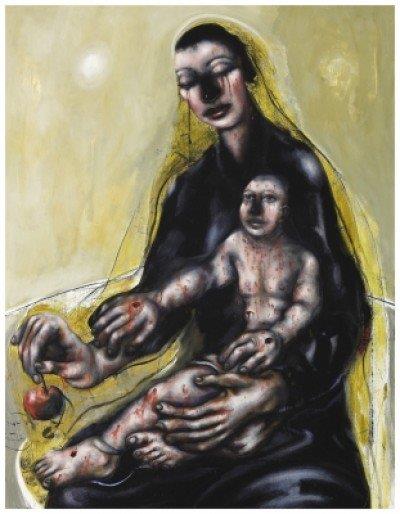

On the cusp of Holy Week our attention shifts from Annunciation and Nativity to Calvary; from expectancy and birth to suffering and death. As we make that move, this painting holds birth and death together; it draws invites us to pay attention to an apple. An apple in the hand of Eve is a symbol of temptation, misdirected desires, and our human propensity to mess things up. An apple in the hand of Mary is a sign of redemption, self-giving love, God propensity to forgive and restore.

Chris Gollon: Madonna of the Apple (2012)

That is the overarching narrative of salvation - of a love that gives in perfect freedom with all the risk of hurt and failure that that entails; and a love that will not let us go when we face the reality of human vulnerability. Steve articulated this drawing on Simone Weil’s theology last week. He identifies the paradox of love – of intimacy and separation. We cannot insulate ourselves from pain – yet we are called to hope in the midst of it. A hope founded on God and the assurance that all shall be well.

Eliot writes that history may be servitude; faces and places known and loved to us vanish, or are renewed. The reality of the human condition is met by grace: Sin is Behovely, but / All shall be well, and / All manner of thing shall be well. All shall be well because our hope is in the faithfulness of God’s love; his yes to humanity. All shall be well because such hope does not disappoint, rather it engenders trust. In stillness, in waves and sea Eliot describes A condition of complete simplicity / (Costing not less than everything) / And all shall be well and / All manner of thing shall be well / When the tongues of flames are in-folded / Into the crowned knot of fire / And the fire and the rose are one.

Hope demands that we inhabit the Gospel story afresh. As we immerse ourselves in Holy Week, that invitation to immerse ourselves in this narrative is more acute. It allows space to ask questions about loss and renewal, grief and gift; questions which are more spacious than answers.

This painting is an impossible moment of infancy and death; eternity caught in a span. It is love with us, the source of hope. Not an ending, but a new beginning. Perhaps we will catch a glimmer of hope and renewal that we come know, with baited breath, like a breaking dawn, as resurrection. That is perhaps conveyed in ‘A blinding brightness’.

Catherine Clancy: A Blinding Brightness (2014)

Denise Inge thinks deeply about this resurrection hope in her book ‘A Tour of Bones’. She discovers that preparing to live and preparing to die are in the end the same thing. She writes about the Spirit brooding over us, refining us, rushing through us and drawing us on. Whispering the assurance: Do not be afraid. As we face the frailty of our human nature we are invited to rediscover hope by placing God centre stage and responding to an invitation to turn, to follow to set our Christ, setting our eyes on him. Do not be afraid. Learning to die well, learning to let go, extends our horizon so that we might live well.

Denise’s journey takes her to various charnel houses across Europe: each places ‘tells’ her something. At Sedlec she ponders the quest to find a lasting hope and the story of resurrection, and hope amidst doubt. For her it isn’t about believing the impossible – but leaving room for the improbable… it is the daring act of staking a claim in the unprovable. That is what makes it hope rather than optimism, because it is active. It does more than wait to see what will be; it acts prior to proof. It is audacious.

Such an audacious hope in resurrection is life-enriching; it is an invitation to live without being afraid. She writes: we think we need a dream. We are urged to ‘climb every mountain’ till we find it… but what we really need is hope. Humans cannot life without it… Hope is not the same thing as optimism. Optimism says that things will get better. Hope says that the good we envisage is the good we work towards. Optimism is largely passive: it is about waiting for what is better to come to you. Hope is active: it goes out and does. It falls and fails sometimes, but it is tenacious and unafraid… it will not let go of the notion that the good is real, and that we can find it.

Have you found a lasting hope? Anchor yourself in the eternal abiding (for me this is God). Feed yourself with something stronger than optimism. You are in a constant state of growth and transition, so let change transform you.

Catherine Clancy: Bird of Hope (2014)

If hope in the resurrection is the paradox of continuity and transformation, then we are drawn more deeply into an act of faith: the sensing of light while it is still night. Perhaps it's an intuition shaped and formed by the Holy Spirit, so often depicted as a bird in flight. There are powerful hints of faith and hope and love; of a deeper communion beyond the dark cold and empty desolation, beyond the waves and the waters. In ‘Little Gidding’ Eliot writes of a dove descending – an incandescent flaming love redeeming us and freeing us from sin and error. Perhaps we should also pay attention to his words in ‘Ash Wednesday’ – words of hope, inviting us to put God centre stage, and allowing our cries to come to him:

Although I do not hope to turn again

Although I do not hope

Although I do not hope to turn…

Teach us to sit still

Even among these rocks,

Our peace in His will

And even among these rocks

Sister, mother

And the spirit of the river, spirit of the sea,

Suffer me not to be separated

And let my cry come unto thee.